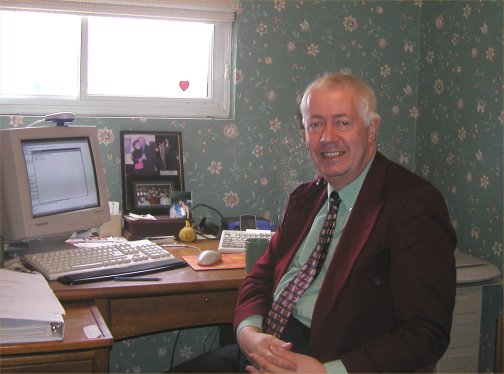

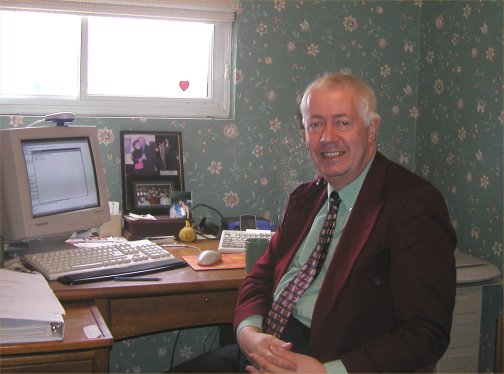

The author of this page. Photo taken at a friend's home in Oakville, Ontario

The author of this page. Photo taken at a friend's home in Oakville, Ontario

Old friends Colin Weightman and Ben Hooper are compiling a book of their happy memories growing up on the Common fifty years ago. They are appealing for other people to send in their tales, memories and photographs of life in the area. Notwithstanding that the book has now been published (see below), Colin still needs material for a further volume to be entitled 'More Common Folk.' They also want to get in touch with old friends. Both of them lived in Sladedale Road. You can contact Colin at Colin . They also now have a web site at: Stories . As they rightly say on the site, 'It is a sad fact that as we all eventually pass on these stories are lost forever. I want to try and record these stories, to preserve some of our rich 'grassroots' social history for future generations to read.'

Their book is now out. 'Common Folk' is one book consisting of two separate large volumes. Each volume is packed with stories and photos. 'Common Folk' is a nostalgic look back in time through this large collection of stories and photographs (in two volumes) to a time when life was a lot slower but also, all too often, a lot harder. When it was harder to make ends meet, the depression, the war years, rationing, and poverty but also stories of happier times, when folk got by on much less and appreciated things a lot more. A collection of stories as told by ordinary folk, in their own words, about what life was like for them and their families in the Plumstead and Woolwich districts in those now far off days.

You can order the book through PayPal at Flatmate Pete Cowley or you can send a cheque in your national currency to 'Stories', PO Box 15-324, Wellington 6243, New Zealand. From the UK the cost is £36 economy mail or £40 airmail. Other prices are: €40, €45; US$, $50, $55; Canadian$, $62, $67; Australian$, $51, $54; South African Rand, 480, 525.

'Our sense of identity is formed by our own complicated life histories, and our understanding of those life histories' - Michael Moran

This is a second edition of the page - the first version was edited and partially re-written in March 2001.

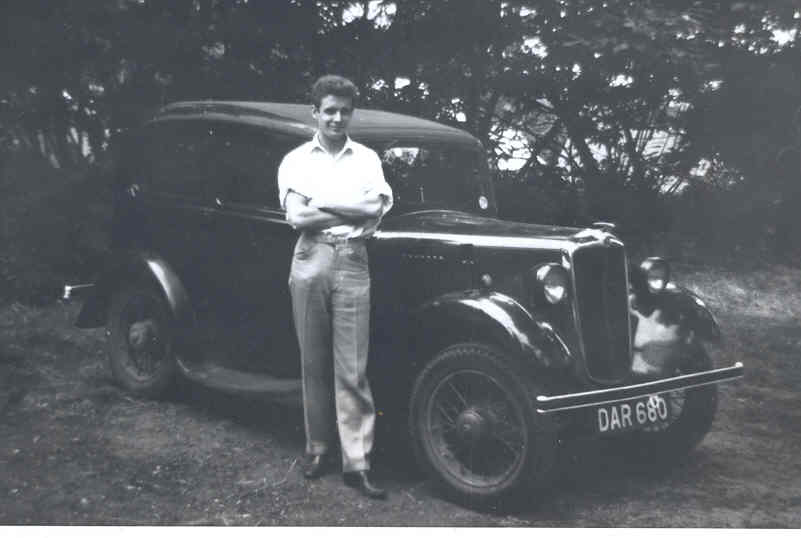

'By the 1960s cars were becoming more common'. The first car that a young man owned was a source of some pride as this photo of a South-East Londoner (and well-known Charlton supporter) shows

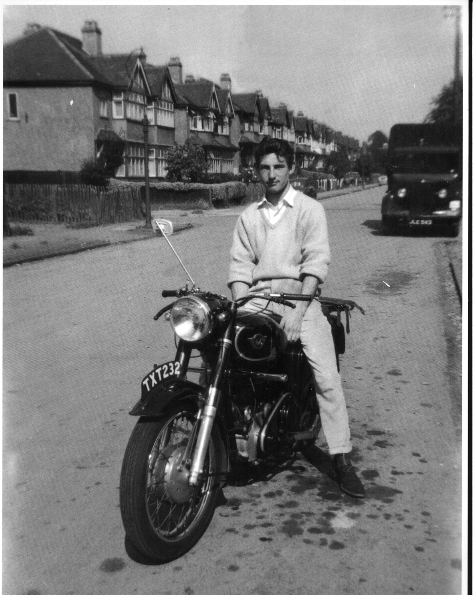

Another option was the motor bike. This young man, somewhat James Dean like in appearance, is a well known Charlton supporter today. Note the absence of any crash helmet in this Catford scene and the patches of oil around the bike that confirm that it is a British make.

That chance visit motivated me to do two things. One was to set up this page. The second was to write a book looking at economic and social change in the second half of the 20th century, but relating it to the stories of people who grew up in South-East London. So far I have made only a tentative start on that project, but it remains a long run ambition. One point worth making is that South-East London was a relatively distinctive part of London. Then it was isolated from the tube network that served so much of London (now less so with the Jubilee Line at North Greenwich). People from South-East London have a distinctive version of the London accent which I eventually identified as having an underlay of the old rural Kent accent.

I have encouraged feedback to this page and some material from the messages I have received is incorporated in the text below. One illustration of what a small world it is came when, as a result of a contact established on the Charlton E mail list, I met in Boston, Massachusetts a Charlton supporter who had lived in the house next door us when he was a child (although after we had left). His mother still lived there and I learnt that the people we had sold the house to over forty years ago were still there and claimed to remember me. In 2003 I went on a holiday cruise in the Baltic. The lady I was sitting next to had been brought up in Plumstead Common and at one time lived in Macoma Terrace which I used to walk along each day on my way to school.

Some visitors have asked me to write on my teenage years in Essex and more specifically on the subject of 'mid-Essex mod culture'. I was invited to make a return visit to Billericay recently to the Cater Museum and Library. The Billericay Society plans to reprint my series of history booklets on the town. So at some point I will add a Billericay page covering the 1960s. A start has now been made on this page. Visit Billericay .

A friend of mine commented that nostalgia about the 1950s was all very well, but 'does not explain the desire to "escape" from the 1950s clearly felt by many folk.' Somewhere I read a reference to the 'claustrophobia' of the 1950s. In a recent article, Manchester University's Mick Moran commented, 'It is salutary to recall what an appalling, repressed, monochrome world existed in Britain in the 1950s and how far we have come since then.' One person who E mailed me commented, 'Our generation was the first to challenge parental precepts; we had disposable income thanks to the security provided by our fathers and we also benefitted from the '48 Education Act, school milk and the Welfare State. We also developed a rebellious streak as personified by the Teddy Boys, Mods and Rockers; and later the Hippies. Whether we belonged to these groups or not, they had a major effect on societal thinking.' Another person commented, 'Life then was simpler, more uncluttered, more focused. We did not want as much. Our only aspiration was to get an education.'

This essay is not meant to be an uncritical celebration of the past and a condemnation of the present. Recalling what he terms a lower-middle-class-London-surburban life in the 1950s, David Lodge writes, 'Its anxieties and privations made us temperamentally cautious, unassertive, grateful for small mercies and modest in our ambitions. We did not think that happiness, pleasure, abundance, constituted the natural order of things; they were to be earned by hard work (such as passing examinations) and even then it cost us some pains to enjoy them.' On the whole, life at the beginning of the 21st century is better than in the 1950s for the majority of people (although clearly there are exceptions such as the homeless and even the 'working poor'. However, for most people life is more varied and challenging, offers more opportunities and is generally less constrained about how one should live one's life.

There is, of course, a downside to the reduction of social control, principally in terms of higher crime rates and of problems such as drug addiction. For some time the Greenwich Mercury had a weekly column by the activist who runs the Plumstead Common Environmental Group and their team of 'graffiti busters'. (There is a link to their web site at the end of the page). By dint of hard and repeated work, they have cleared their immediate area of graffiti. Recently when they were cleaning graffiti they were abused by a gang of youths making threats, who then returned with masks over their faces to make further threats and finally retreated to put graffiti on the nearby bowling pavilion (from where they were chased off by the police). Such a sequence of events would have been unthinkable on the Common in the 1950s.

One of our correspondents referred to the growth of crime in the area and to the fact that there seemed to be more population turnover. He commented, 'The area has gone downhill in the last few years with the down turn of the property market, people are now so interested in their lives within the immediate vicinity. There has been a high transition rate - many houses being sold, so new people moving in, so losing out on the network ties. It's a shame really because it is physically a really nice area with wonderful views over London. There are repeated break-ins to property and cars - the police are indifferent and claim it's the kids from the Barnfield Estate, but never seem to catch anyone. Having said that I have never felt unsafe in my own home and people do leave us alone.' For some very positive comments about living in Plumstead today go to Plumstead today . Also worth visiting is a new blog on Plumstead Common Plumstead Common

Life in the London suburbs in the 1950s was safe, secure and orderly, which was what people wanted after the upheavals of the war, it could also be dull. Somewhat controversially, Mick Moran writes, 'I don't have any doubt that the world of 2000 is immeasurably better than the world of 1950: no sane person would want to return to that world of snobbish hierarchy, sexism, homophobia, race prejudice and, in the Celtic parts of Britain, rampant religious bigotry - not to mention the world of unregulated motoring, uncontrolled insider dealing, the callous indifference of professionals to clients.'

Social class mattered in the 1950s in a way that it does not today. As Moran puts it, 'This was a world of hierarchies organised along lines of gender, of class and of race.' The area in which we lived is marketed today by estate agents as 'Shooters Hill slopes'. For those of you who do not know the area, Shooters Hill is one of the highest pieces of land in London. At its summit is Oxleas Woods, fortunately spared from the ravages of a new road planned for a projected East London River Crossing. Further up the hill from us was the Laing's Estate, built by a prestigious firm of house builders and regarded as 'the' socially superior place to live in the immediate locality (but not enjoying the social cachet of parts of Blackheath). The headmistress of our primary school lived there and we had distant relatives by marriage who had a house backing on to Shrewsbury Park. Ironically, I never entered the house until my uncle's funeral in the 1980s.

There was an interesting item in the Mercury recently about an unusual second world war air raid shelter in the garden of two houses on Ashridge Crescent on the estate. It was a large and elaborate concrete shelter with electric power. There was some speculation that it might have been a clandestine base for Home Guard cells in the event of an invasion. However, people who once lived in the houses report that it was built by two neighbours who had relevant skills, one being a demolition contractor and the other working for the electricity board. There is still some question about whether this was a cover story. However, we had friends in Camberwell who had the foresight to build a reinforced concrete shelter well before the war broke out. Some years ago when they were still alive it attracted a visit from the Camberwell Society.

The area down the hill towards the river was occupied by Victorian houses of moderate quality. For an excellent survey of the development of Plumstead as a suburb from 1800 to 1900 visit Plumstead 1800-1900 . One correspondent recalls lower Plumstead as a 'settled lower working class area.' Much of the area was rented then and some of the houses have now been converted into flats. So we were in an intermediate social zone in which the aspiration for 'respectability' was the defining norm. People in our road worked in such jobs as shop assistants, lorry drivers, postal sorters or various kinds of skilled workers. One correspondent recalls being 'a merchant seaman as a traditional form of employment for the area.' Local people aspired to better things in the world. One correspondent referred to his mother and father taking 'the bold step of buying a corner shop in Malton Street, Upper Plumstead.' Ostentatious display was frowned upon in our close. When one resident decorated the front of his house with red, white and blue illuminated bulbs for the coronation, this was regarded as exceeding the bounds of acceptable behaviour. It is interesting to contrast this rather settled world with Mick Moran's comment: 'When my father migrated to Birmingham from Ireland in 1953 he had no difficulty in finding work (after all, the state had locked up several hundred thousand potential competitors in National Service); finding lodgings was a different matter in a city where boarding houses routinely sported notices announcing "no blacks or Irish"'.

Quite a lot of social control was exerted over children. Playing in the traffic free road was possible and permitted, but there were strict boundaries. If games of hide and seek took us into the back passageways between the roads, irate residents would appear at the doors of our parents to complain about the noise, disturbance and invasion of privacy. Similarly, attempting to play hopscotch on the pavement led to complaints about the chalk marks.

Just a mile or so away from all this suburban respectability was a different, much less respectable world. Woolwich was, after all, a garrison town. In its issue of 18 March 1955, the Kentish Independent published a feature on night life in Beresford Square at the heart of Woolwich. The story was printed in the usual close gothic type, but the tone was clear enough, if rather melodramatic: 'Day gives way to night in Beresford Square ... Some [of those there] have criminal records, others balance on the knife-edge between the legal and the illegal, and often there are prostitutes out on patrol.'

If this was not enough to make the residents of Shooters Hill choke on their cornflakes, the article had some revelations on the use of bad language. 'Bad language (which is much more prevalent among all classes of society than is generally realised) can be heard anywhere. When bad language is allied to obscenity, however, and used most unstintingly in the presence of immature girls, the effects can be far-reaching.'

The emergent youth culture was also in evidence. 'The "Teddies" were more in evidence in a cafe. They were noisy and boisterous in their actions, but there was no real trouble.' Should there be, 'two policemen were silhouetted against a window.' Social control was reinforced by the long arm of the law. What is lawful today was punishable then. An issue later in the year notes that a fine of three pounds was imposed 'for loitering for the purpose of betting.'

Beresford Square was, of course, different in the daytime when the market was on. One of our contributors wrote, 'Nan and some of the other stall holders had lock ups in the rear yard of the public house next to Woolwich Arsenal station, think it may be the Royal Oak. Who remembers the French Onion Johnnies in the 1950s and how they carried their bunches of onions all over the Woolwich area on the handlebars of their push bikes selling them door to door. Can recall a couple of names, Pierre and Simeon, and all the family were good friends of Nan. They had the hay loft above the stables and entry was a very steep wooden staircase. The loft is where they tied the loose onions into bunches so they could be hung over the handlebars and many an hour was spent playing and hiding in all the straw which seemed to cover the complete loft. The mum made the most delicious tomato soup from all the over ripe tomatoes given to them by Nan. You couldn't beat it on a cold day with French bread, yet another part of Woolwich gone.'

Some of the biggest changes have taken place outside the home in the world of work. The 1950s was a time of full employment. Once people had a job they expected to keep it, perhaps for a whole lifetime, or if they didn't like it they could find another one. Another big difference was that the world of work was principally the world of men. Apart from my aunt, who helped my uncle in his newsagent's shop, most of the women I encountered in my childhood who worked were single. (The main exceptions I can think of were of a minority of women teachers and our family doctor who was a middle class socialist who lived in Blackheath). One person who got in touch commented, 'I will take issue with your statement on married women not working. I seem to remember many women having to work in Plumstead to make ends meet, such as part time shop workers, cleaners in cafes and pubs, also taking in work such as lampshade making to name a few examples that come to mind.' This suggests that the social distance between 'lower' and 'upper' Plumstead was greater than I realised at the time. But among the skilled working class/lower middle class people who lived in our cul de sac, the unspoken assumption was that married women with children did not work. As The Wartime House notes, 'A suburban wife who worked could be a source of shame to her husband as it implied that he did not earn enough to keep her.' Today, of course, most women work, although they are more likely to be in part-time jobs than men.

Another difference was in working hours. It is, of course, the case that working hours in Britain today are long, particularly compared with other European countries. People in professional and managerial occupations, or those who run their own businesses are self-employed, have particularly long hours. In more routine jobs overtime may be necessary to earn a living wage. However, in the mid 1950s most people were expected to work on Saturday mornings (although some got away with every other Saturday). This practice came to an end in the early 1960s - it was always rather inefficient, because it meant commuting to work for a short working day when probably very little was achieved. But think of how differently your leisure time would be structured if you had to work on a Saturday morning.

The majority of women, then, were expected to perform a domestic role. A wider range of (supposedly) labour saving devices were only just becoming available in the 1950s. My mother and grandmother conducted the weekly wash on Mondays using a copper which boiled the clothes. Water was then extracted using a mangle before they were hung out to dry. 'Hoovers' were in most homes, but a fridge was still a rarity, let alone a freezer. This affected the preparation and storage of food. With modern food distribution systems, much food was still seasonal in character. We often had gluts of food from our allotment (see below) such as runner beans. Most people still ate rather traditional foods based on an English cuisine. Indian food, Chinese food and pizzas, which most people eat today, were still unknown in suburban circles. The range of food obtained from a series of specialised shops (grocer, greengrocer, butcher) was relatively limited compared with what is on the supermarket shelves today. I did not encounter an avocado pear until I was a teenager. In my view, even traditional English dishes are cooked with more flair and imagination today than they were then.

A recent story in the Greenwich Mercury reminded me of our allotment. In fact, we had two, next to each other, no doubt a hangover from wartime 'Dig for Victory' efforts, although half of one was overgrown with an impenetrable blackberry patch. At weekends my father would head off to tend the allotment. Shortly before we left Plumstead Common we heard that the allotment was going to be used for housing by the council, more specifically old people's bungalows. With 'right to buy' legislation most of these seems to have been sold off and occasionally one sees one on the market. A recent item in the Mercury referred to the fact that residents were being plagued by Japanese knotweed on abandoned land, the ownership of which was uncertain. Looking at the photograph accompanying the report, the problem area evidently overlooked the back Tuam Road in a similar location to our allotment. Perhaps it should have been allowed to stay as an allotment. There were also extensive areas of allotments stretching behind Cheriton Drive up towards Shrewsbury Park, but most of these are now abandoned and overgrown.

In my days, St.Margaret's had some good teachers, one of whom I kept in touch with until I went to University. Another was quite a successful writer of adventure novels for children. In general, though, primary education in the 1950s was not as challenging and interesting as the education my children received twenty-five years later. Maths was taught by the endless chanting out loud of tables combined with repetitious exercises from books, while English was taught through exercises which largely consisted of filling in the appropriate blank sentences in words. I don't think that I was challenged or stimulated sufficiently in primary school, and I would say much the same of secondary school, although at least there I was able to fight back by causing endless trouble for the authorities. Only when I got to the sixth form did I consider that I was intellectually challenged in any way.

One person who made contact with me from abroad commented, 'I was hoping there might be some mention of Kings Warren School (later Plumstead Manor) on Plumstead Common where I went to school on the 53 bus every day for seven years. You must remember the jolly-hockey-stick gels with their straw boaters - the boys from Bloomfield Road used to try and pinch them and fling them out of the bus window.' King's Warren was opened in 1913 and was once known as the Brown School because of its uniform. My mother had a place to go there at the end of the First World War, but it was not taken up. Fees were then £3.33 a term, a tidy sum in those days for a middle income family. Around that time my aunt was ill requiring daily visits from the doctor. At the end of each visit he would outstretch his hand at the bottom of the stairs for 2/6d (12.5p). That amounted to nearly a pound a week, a substantial sum when five pounds a week was a good salary.

A recent article in the Greenwich Mercury's Down Memory Lane feature reminded me how central a part the Co-op played in our lives in the 1950s. The article is about the shopping parade with its distinctive clock tower built at 'The Links' at Plumstead Common by the Royal Arsenal Co-operative Society (sometimes irreverently known as Rob All Customers Slowly). It's where we did much of our shopping with the Co-op also delivering bread and milk by horse and cart as well as a Christmas hamper in a wicker basket.

A historic photograph of the 'Links' shopping parade at Plumstead Common

As the years went by, the Co-op lost its market share. As people became more prosperous, the 'divi' paid to Co-op members lost its attraction, and its goods seemed less sophisticated than those of its emerging competitors. We moved away from what Moran calls 'a world of deferential citizens and grateful consumers'. The Co-op also suffered from the spread of car ownership: its stores were in traditional shopping parades or, as at Plumstead Common, formed suburbanparades. The picture in the Mercury article, taken in the 1930s, shows just one car outside 'The Links' and the pavement busy with pedestrians. Not what one would see in Plumstead Common road today. I haven't been past the 'stores' at Plumstead Common for some time, but last time I was there it was a shadow of its former self.

Another major store in Woolwich as Cuff's. I remember going to see Father Christmas there. One correspondent recalled it as an 'Aladdin's cave'. It used to have vacuum chutes taking money tendered by customers back to the office: the change and a receipt came back then. (Another, older store in Hare Street, a kind of haberdashers, had a wire and pulley system - I can't remember the name of the store). As these systems slowed down transactions, presumably they were there because the sale staff were not trusted not to pocket money. Cuff's was apparently part of a small chain of department stores. It closed about 1984/5 and was knocked down as it was full of asbestos. Woolwich picked up a bit as a retail centre in the 1970s when Sainsbury's, Littlewoods and W H Smith opened stores, but has been struggling in recent years. I have been told that there are plans for a major demolition and rebuilding. Someone cynically remarked that it would be to create the biggest one pound store in the world, but perhaps developments at Woolwich Arsenal will regenerate the area.

One big difference in those days was that there was an acceptance of levels of pollution that would not be tolerated today (of course, the problem in London now is of pollution of the air from 'mobile sources' as cars and lorries are referred to). However, in the 1950s there was bad air and water pollution in London. The combined output of industry and domestic coal fires in the Thames Valley produced 'peasouper' fogs when one could only see a few yards at most. The most notorious example was in 1952 when large numbers of people were killed. This catastrophic event led to the Clean Air Act of 1956 and the institution of 'smokeless zones'. However, the real progress was technological rather than legislative: the advent of gas fired and other forms of central heating offered less labour intensive forms of domestic heating - and also meant that effective heating was not confined to one room of the house. As far as water pollution was concerned, it was actually possible to smell the Thames on Plumstead Common (well over a mile away) on a hot summer's day. And when the wind blew from the direction of the cement plants at Greenhithe, a gritty dust would be deposited on the window sills. Then, of course, the whole emphasis was on production and problems of the environment were hardly recognised at all - or, at least, only as health problems. In many ways, the years of austerity makes the notion of recycling very acceptable to someone of my generation.

Earlier versions contained nothing about health and this perhaps reflects the fact that I did not have a serious illness until 2004 when I was taken ill on the Jubilee Line after leaving North Greenwich and ultimately found myself undergoing unanticipated surgery. My grandfather, Thomas May (picture below) died in 1934 when there was no health service. He was ill for about two years before he died from prostate cancer and cardiovascular disease and I recall my grandmother telling me about how the doctor would hold out his hand at the bottom of the stairs for a half a crown (two and sixpence, i.e., 12.5p) after each visit. I grew up under the National Health Service which has existed virtually all my life. In the 1950s the doctor was almost a member of the family. Our youngish woman doctor (early thirties?) would faithfully drive over from Blackheath to Plumstead Common whenever someone was ill. She was unfailingly through and kind (I particularly remember her being so when I was dispatched at the age of seven to send for her after my grandmother died). She was very committed to the National Health Service which she thought was helping to build a better society, as in many ways it was. Today, of course (for very good reasons), doctors work in a group practice and the personal relationship is no longer there. Our group practice when recently advertising a new post described home visits as 'a necessary evil', limited in the practice by the fact that the affluent and educated clientele realised that they could often be avoided. If I was a doctor, I would not want to be called out at all hours for problems that could wait until the morning.

Much has improved in the meantime. Paradmedic interventions help stablise patients until they can reach hospital. The notion of the 'danger list', spoken of in terms of hushed awe, has been replaced by professional intensive care. When I had my operation, there were two crucial differences from even a few years ago. I did not have to be cut open. The anesthethist suggested I have a spinal rather than a general so I was able to spend the forty minutes in theatre chatting to him about Australia. Anyone who can remember dental treatment in the 1950s will be grateful for today's more sophisticated treatment. At one time having one's teeth removed and being fitted with dentures was seen as a positive milestone. Today, the emphasis is on conservation dentistry and everything is done to make the patient comfortable. I feel relatively relaxed about visiting the dentist, although my dentist does not like using any form of anesthetic but I drew the line at having a root canal done without one. And, of course, it's no longer possible in practice to get NHS treatment which means that many people get no treatment at all.

The immediate wider world was geographically quite a small one. Reading recently the book The Best of Times: Growing up in Britain in the 1950s I was struck by the comment, 'For us, as children, the life of the immediate neighbourhood loomed large.' For me as a frequent user of the Internet and someone who travels quite extensively, the contrast is quite a striking one. I had not thought before about how geographically confined and focussed on a small area my life was in the 1950s.

Perhaps its most important, vibrant and exciting part of this immediate wider world was The Valley, home of Charlton Athletic Football Club. More about that later. Three regular trips always gave me pleasure. One was to ride on the trams (I still have my Last Tram week ticket) to Well Hall Pleausance at Eltham, a pleasant set of gardens with ponds full of fish which fascinated a small boy. When I was last there, the ponds were empty, but the gradens were re-opened after a major restoration in December 2002. Before re-opening them, it had been necessary to install a security system following vandalism. There have been repairs to the Tudor moat, garden walls, water features and fountains, and the park has a new sunken garden and a rockery.

A second trip was to my aunt and uncle's house in Belvedere, then officially in Kent and with green London Country buses going past their window. They were slightly more affluent than we were and had a large garden with a steep slope with meandering paths in which I can play. Some of the garden ornaments are in my garden today and I hope that my grandchildren will be enchanted by them in time (Victoria already is). A third trip was to relatives in East London. All being well, this would involve a trip on the Free Ferry (rather than walking through the dismal tunnel), then operated by paddle boats with a vague American flavour. There is a good web site on the Woolwich Ferry at Ferry .

The free ferry has run in some form since the 14th century. It is used by a million vehicles and two million passengers to cross the Thames each year. It can take lorries that are too big to use the two tunnels under the Thames (Blackwall and Rotherhithe). In March 2008 Greenwich Council announced that it would cease to operate the service. In October 2008 operation was taken over by Serco which also runs the Docklands Light Railway (being extended to Woolwich). The timetable for the two-boat ferry service is to remain unchanged running from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. on weekdays with a reduced service at the weekends. As I recall the service, it ran with three boats at the busiest times (quite a challenge), two boats off-peak and on Saturdays and one on Sundays. For some great photos of the Ferry and river, but also of Plumstead Common and Shooters Hill go to Photos . Then, on the other side of the river, perhaps the bus would be halted by a 'bridger' as a boat from some exotic port entered the Royal Docks.

One of our contributors has sent in some memories of life in Belvedere in the 1950s when it certainly seems to have had a rural feel. He writes: 'Picardy Road was always referred to as Picardy Hill. We spent many a time trying to cycle up the hill without stopping and cannot remember ever making it to the top. The closest I recall was around Bunkers Hill, a fair few metres from the top. Even the London Country bus (491?) had trouble, not stopping until it reached the bend at the top just past Fremantle Road. Life in Belvedere in the early 1950s for mum and dad raising three kids was difficult as money was short, but life was simple and as kids we amused ourselves around the village. It would be hard for kids in Belvedere today to imagine the meaning of the village life that we experienced prior to the advent of the motor car and television. Life for us was simple with no expensive toys or computers to keep us amused and life always seemed an adventure, exploring on foot an area from Bostall Woods in the west, the Thames river bank to the north, Erith to the west and Streamway to the south.

One can clearly remember the cattle, and the corn being grown, on the marshes now Thamesmead; a pig farm at the bottom of our road (Ruskin Road); even the pig bin for collecting food scraps positioned in Lessness Park Road; scrumping apples, pears and plums from the orchard, now the lower part of Clive Road. Milk was still delivered by horse and cart and they were stabled behind Buckinghams, the butcher on the corner of Nuxley and Hodd Road in the village. The village bobby was a person to keep clear of, as not only did he clip you around the ears when caight, but he would take you home to ensure further punishment was dealt out by the parents. Who would remember Saturday morning pictures in Erith at the Regal, Odeon or 'Pom Pom' at the bottom of Friday Hill. Can recall being given 1/3d by mum, 3d each way on the red bus (no.99), 6d entry and 3d for sweets and ice cream, a real treat! We even did better than that as we walked one way so an extra 3d (1.25p) was saved for goodies. One sometimes wonders what our children and grandchildren would have made of all of this, knowing the pressures they are all under today, in many ways they were the good old days.'

However, there were two glimpses into a much wider world which have influenced me until today. The 53 bus from Plumstead Common Road was the most immediate route to a wider world and played a big part in our lives. In a recent item in the Greenwich Mercury , a reader reminisced in response to comments on the 51 route, 'What about the noble 53 ... so many SE Londoners' taxi service to John Lewis and the West End. The 53 has taken me over the years to spend birthday and Christmas money up town (and in Woolwich when it still had Cuffs), to London Zoo when it ran all the way to Camden Town (a great tragedy when they withdrew that section of the route), to my first job after university, and to connect with a train to Bluewater last summer when I was 8.5 months pregnant and found it difficult to get into a car.'

One of my favourite parts of the route was when it would take one over Westminster Bridge, past the House of Commons, up Whitehall, through Trafalgar Square, Oxford Circus and eventually to the much loved London Zoo. I was soon fascinated by what when on in the Palace of Westminster. By the time I was eleven or twelve, I managed to see prime minister Harold Macmillan driving off from Downing Street to the House and I had got into the House itself and met a MP. My appetite for all this was fuelled by the discussions that would take place in my uncle's newsagents shop in Lakedale Road late on a Sunday morning when my father went to collect the papers. With the shop quiet, and the gas lamps hissing gently, there would be much talk of 'reading between the lines' in the day's papers. Some of it, of course, was above my head. What exactly was it about Tom Driberg's reputation (he was a columnist in Reynold's News which was so unusual?

There was also a contact with a wider and more exciting world. Somewhat unusually, our house was named after a state of the union (Virginia). From time to time, letters would arrive from our relatives in the southern states where some of them were involved in courthouse politics. Most exciting of all, one of them might come to Britain, and we would be swept off to a Park Lane hotel for a meal. Naturally, I was fascinated by this country, glimpsed through movies, where people seemed to be so rich and where every other person seemed to be a gangster. It is perhaps no accident that today I have an American social security card and ID. I have written extensively about the States and (apart from being at The Valley) feel most at home driving down the Interstate listening to some contemporary country and western or soft rock.

Saturday afternoons at Charlton were the highlight of the week. On 11 January 1947 my father went to watch Charlton beat Rochdale in the FA Cup. Then he walked up to St.Alphege's Hospital in Greenwich where I was born at 7.30 p.m. I have been trying to work out when my father first started supporting Charlton. He was born in North Woolwich, that odd bit of Kent across the river, and I think that his loyalties were originally divided between West Ham and Charlton (he was at the famous first cup final at Wembley involving West Ham). He also played non-league soccer for a team on that side of the road (certainly the only time he went abroad was to play soccer in France and Belgium). However, his older cousin Ted was a Charlton supporter and when the family moved to the Progress estate at Well Hall, my father's loyalties switched firmly to Charlton. As a youngster, he made money for tram, admissions and refreshments by looking after horses while the owners made commercial deliveries (the horses could be frightened by the growing volume of motor traffic).

When I was six years old, I was judged old enough to accompany my father to games at The Valley. As one of my correspondents noted, 'becoming a supporter is a rite of passage; apart from one's schooling, which is chosen for each child, joining a group of football supporters is the first personal choice an individual can make.' He added, 'I hated grammar school, so my Saturday strolls to The Valley gave me both the privacy and group membership I've sought ever since.' The football magazine 4-4-2 recently summed up the attractions of football as a release from everyday life well: 'the regular holiday from measured argument, a justified opinion, a consistent viewpoint and a civilized tongue'. In my case, as for many others, the choice of which team to support was made for me, but I am glad it was. I can't remember the first game I went to, but an early home game I do remember was when Charlton beat Liverpool 6-0.

My grandmother was born in 1875, thirteen years before the Football League started playing, but nevertheless identified with Charlton which is perhaps not surprising given that she moved to the area at around the time the club became professional. She took a keen interest in football form, although admittedly that was partly from a gambling perspective, pursued through a close study of the Racing and Football Outlook . It was always a pleasure to discuss with her promotion and relegation prospects in which she took an intense interest, even though she was around the same age as the modern organised game (the FA Cup started in 1871, but Wanderers and Old Etonians have long since disappeared).

The Valley was built in an old chalk quarry. With its terraces, particularly the vast East Terraces where we stood, it was capable of holding over eighty thousand people in its heyday. In the early 1950s, crowds of over forty thousand were far from unusual, although they tended to drop by two thousand if [Woolwich] Arsenal were playing at home that day. When I went to buy my tickets at The Valley for the playoff final, Arsenal had just won the double and there were a number of Arsenal supporters on the train returning from the celebrations. Some even got off at Charlton.

On a match day we would walk down to Plumstead Common Road and catch the 53 bus and join the large crowds walking through Maryon Park to the ground. Charlton itself is something of a curious mixture. I recently got hold of a second hand copy of How People Vote, one of the first studies of voting behaviour in Britain based on the 1950 general election in Greenwich. It refers to Charlton Village 'with its superb Jacobean manor house, its charming church, and its homely inn, [lending] some grace to the raw new housing estates around, like a Windsor chair in a pre-fab.' It continues, 'The residents of Charlton, perhaps because so many of have long dwelt under the chastening influence of a manorial regime, have a curious betwixt-and-between uniformity of style.' Make of that what you will. Continuing our journey past the deer and other animals caged in the park, it was then a short distance to the ground. Once through the turnstiles, and having walked across what seemed to a small boy like a sea of scrunchy pebbles, we turned on to the entrance to the East Terrace which gave you a buzz of excitement as the rapidly filling arena was surveyed. Just before the match started, my father would sometimes point out Stanley Gliksten assessing the size of the crowd.

One of my correspondents recalled his first visit to The Valley at the age of six: 'I don't remember much about the match but I do remember the big red rosette my Dad bought me, the song they played over the PA - when the red, red, robin comes bob, bob, bobbing along and how excited I was at the noise of the crowd in the stand with me shouting "Charlton, Charlton" at the top of my voice. I also remember being puzzled at why people clapped quietly when the ball was passed back to the goalkeeper ('what's so special about that?', I thought in my innocence). Dad also knew one of the reporters and I found myself in a room under the stand at what I later understood to be the post-match press briefing.'

More often than not the pitch was a quagmire. The fluent passing play Charlton seek to provide today was impossible under such conditions. Better drainage, higher standards of groundsmanship and the right sort of grass have all contributed to better playing surfaces today. No longer does a player's skill include making ingenious use of puddles, as reported in one programme from the 1960s. Remember also that the game was played with a leather ball to which the mud readily adhered.

Charlton were a leading first division side then, if a somewhat quixotic one. David Lodge recalls in one of his novels, 'they were always an interesting team to watch, fickle and unpredictable, but capable of heartwarming flashes of brilliance. More than once he and his friends left the Valley a few minutes before the end of the game, dispirited by their team's poor performance, only to hear, as they passed through the quiet, car-lined streets, a huge explosive roar filling the air behind them, indicating that Charlton had scored a last-minute goal and snatched a point.

One of my favourite players was the goalkeeper, Sam Bartram. Sam was a rather unorthdox goalkeeper who took a lot of risks by coming off his line. He never fulfilled his ambition to score a goal himself. One day, to my horror, Sam was not in the goalmouth: my father told me that he had been injured in training. (A bit odd considering that training in those days usually consisted of running around the pitch or up and down the East Terrace to build stamina). Fortunately, the reserve goalkeeper, Eddie Marsh, proved equal to the occasion and we beat Cardiff 3-2. The kind of loyalty that Eddie showed to the club is almost unknown today. He was reserve goalkeeper throughout the Bartram era, but he stayed with the club, although he knew that he would only get a game when Bartram was injured.

Of course, the side did not just consist of the goalkeeper. One of my favourite players was Eddie Firmani who subsequently went to play in Italy and then returned to Charlton at a later stage of his career, finally as manager. It was good to see him at The Valley not so long ago and also hear from his son by E mail. One correspondent pointed out that I had failed to meet Stuart Leary, so I am remedying that omission as he was one of my favourite players. He made a total of 402 appearances for Charlton, scoring 163 goals. In The Valiant 500 Colin Cameron names him as the best player he has seen wearing Charlton colours. He was often acclaimed by the press as the best centre forward in the country, but was denied an England place because of the ban that was then in place on non-English players representing the country (although he had played at Under 23 level). After being effectively dropped by Charlton, he later returned to South Africa and coached black players. He died in tragic circumstances in 1988, his body being found on Table Mountain after he had been missing for five days. Another player who sticks in my memory was 'Squib' Hammond who in those days was what was known as a wing half, i.e., a midfield player. I think that in 1953/4, Hammond played in every match. As the book on Charlton players, The Valiant 500, notes, he never set The Valley alight. But a balanced side needs players like Hammond who are not stars but make their contributions in a solid and dependable way. Steve Brown was a recent example - 'Stevie Brown, he'll never let you down.'

One of my E mail contributors used to live near 'the rangy right back John Hewie ... I don't ever remember him smiling. His honest graft, however, was always something to admire. Support of Charlton, I surmise, is essentially British in that we Londoners generally appreciate honest endeavour above flashiness. Certainly, talent is important but week in, week out professionalism and team loyalty have long been the hallmarks of our club.'

Charlton were relegated from the first division and just missed getting back the next year after losing at home to Blackburn. They eventually fell back to the then third division for a while. Attendances slumped with one home match against Halifax attracting fewer than 4,000. The Valley started to crumble and the East Terraces were declared unsafe. The new owners decided to move the club several miles, and an inconvenient journey across South London, to Crystal Palace's ground at Selhurst Park. Under Lennie Lawrence's leadership, they managed to get back into the top division and hang on for a few seasons.

The supporters wanted to return to The Valley (although another site in the vicinity would have been acceptable) but there was opposition from Greenwich Council. This was overcome by the formation of the Valley Party which won over 14,000 votes in the local elections. The story of the fight to return is told in Rick Everitt's excellent Back to the Valley , probably the book I would take to a desert island. It is as much a story of local political action as a soccer story, but then Rick is a politics graduate. After a spell at Upton Park, and partially funded by the sale of Robert Lee to Newcastle, the club returned to The Valley in December 1992. Only three sides of the ground were open, but it was a start. As Supporters Direct has commented, 'there is much reference to the role of clubs within their communities, but much less reference to the fact that the clubs themselves are communities. The stadium functions as a group hom, and whilst not owned by them in the manner of one's own home, it is a repository of memories; of previous generations; of good times and bad.'

Having a demanding job, a growing family and living in the Midlands, my relationship with the Addicks became tenuous. When the last of the children left home and we became empty nesters, I felt it was time to stop being an armchair supporter. The first time I went back was rather curious. A colleague was a Burnley supporter, and he got tickets when the Clarets were away to Charlton in the cup. So I had the odd experience of sitting in the Jimmy Seed stand, looking over to the building works on the old East Terraces, and sitting mute in my seat while Charlton trounced Burnley 3-0.

My mother's final illness delayed my plans to return, but in September 1994, a few weeks after her death, I was back at The Valley and soon had a season ticket. The 1994/5 season was rather frustrating. Although never in any real danger of relegation, Charlton finished 15th. 1995/6 was more exciting, with Charlton ending up in a play-off position, unfortunately losing out to Crystal Palace. We also had exciting cup runs, beating Wimbledon in the league cup and Sheffield Wednesday in the FA Cup, finally losing in the FA Cup to Liverpool at Anfield.

With the talented Lee Bowyer sold to Leeds, 1996-7 was another disappointing season. We finished up in the same league position (15th) as two seasons before. In 1997/8 we were fortified by the arrival of Sir Clive Mendonca and we got to the play off final at Wembley. What followed was an incredible match against Sunderland which will always be remembered by Charlton fans. After going ahead with a Mendonca goal, Charlton went behind twice until Richard Rufus scored his first ever goal for the club in the closing minutes of the second half to make it 3-3. Sunderland went ahead again in extra time, but a Mendonca hattrick saw the match decided by a penalty shootout. Charlton won this 7-6, replicating a famous victory against Huddersfield in the 1950s.

Charlton were not really ready for promotion: probably the plan was to go up the following year. The skill of manager Alan Curbishley could not offset the limited funds available to purchase players. One great purchase was Chris Powell, later to play for England. For the last phase of the season, I was working in Seattle and had to get up at 5.30 in the morning to go to the English pub to watch the game or listen on my computer at work. Charlton battled on until the end of the season, but eventually finished third from bottom.

Charlton fought back with spirit the following season and ended up as Nationwide Division 1 champions, although they faded towards the end of the season. The pundits predicted as usual that they would be relegated, but excellent home form, and improving away form, placed them in the top half of the table in the second half of the season and out of relegation danger, leading to an eventual finish in ninth place. They finished fourteenth in 2001-2, but after an uncertain start in 2002-3 were in a comfortable mid-table position by Christmas and eventually finished a somewhat disappointing 12th after fading, as they often do, late in the season.

By the end of 2003 they were fourth in the Premiership, having beaten Chelsea 4-2 in an exciting Boxing Day encounter. That position could not be sustained, but the target of a top half finish, hopefully better than 9th, seems to be realistic with the home game against Southampton still to come. Charlton once again have had a better away than home record. When we were battling to stay in Division 1, with a mixture of ageing journeymen and callow youth producing some poor football, the crowd always got behind the team. Now the negative site of football is coming much more to the fore, people whose real satisfaction comes from dealing with the disappointments of the week by slagging off their team. Incredibly, there are quite a few supporters who want to get rid of Curbs on the grounds that 'he has taken the club as far as he can.' But how far can one take a club that still ranks 17th in the Premiership attendance league and has arguably been punching above its weight? The extent to which the crowd is nervous and soon gets on the team's back became even more apparent to me when I had listen over the computer when I was unwell. The prudent strategy followed by the Charlton board compares well with the experience at Leeds, but will it be possible to keep the expectations of the 'fans' (some of whom probably come because it is an inexpensive way to watch Premiership football in London) to a realistic level? There are plans to expand the ground, but can it be filled other than for the biggest matches?

Ever since, Alan Curbishley left his manager the story of the club has been less happy, although by the time he left he had probably become a little stale. I was his first team kit sponsor and got to know him quite well. He strikes me as a person who has great inner calm and is also an excellent judge of people, as well as having the social skills to relate effectively to people from a wide range of backgrounds. Although he made the occasional mistake, he was an excellent 'man manager', as exemplified by the way in which he has won the respect of the fiery Paolo di Canio. When I was ill in April 2004, Alan took the trouble to sign a special get well card with a photo of both of us on the front. Under Iain Dowie and then for a short period with Les Reed as manager, Charlton's performances deteriorated and Alan Pardew could not prevent relegation from the Premiership. Under his stewardship the first season in the Championship was a mixed and inconsistent experience. In October 2008 it was announced that a proposal had been received for the club to be acquired by a company linked with the royal family of Dubia, thus opening an important new chapter in the club's history and bringing it into the 21st century world of sovereign wealth funds.

Because my father worked for British Railways, we were entitled to 'privilege' tickets with which we could roam the whole country. These free travel facilities meant holidays in Cornwall, Devon or Scotland (ultimately at Easter in Cornwall and the summer in Scotland). These seaside holidays, taken in a rented cottage or sometimes on a farm were (in recall at least) always idyllic. The sun always seemed to be shining and the beaches always seemed to be sandy.

The privilege tickets system also allowed us to take days out during the summer. A favourite trip was to go on the train to Frinton in Essex where the sea always seemed a long walk from the station. After enjoying the sandy beaches of the 'select' resort (patrolled by beach inspectors to ensure a proper standard of decorum) we would walk along the crumbling cliffs to Walton-on-the-Naze to enjoy the amusements on the pier (the ghost train was always a favourite and sometimes we would take the miniature train out to the end of the long pier). Some shrimps might be enjoyed in Walton, and then in the buffet on the train on the way back, as the Britannia class locomotive pulled us at speed, we would enjoy toasted tea cakes.

When I was a small child, television had not really established itself again - like many people, I first saw when I watched the Coronation on a ten inch screen. Radio remained important with programmes such as Childrens' Favourites with Uncle Mac on a Saturday morning, and Childrens' Hour at 5 in the evening. Broadcasts reflected the culture of the period. Moran notes 'the ubiquity of strangulated upper class tones on the BBC; the extraordinary public obsequiousness in the face of even the dimmest and most marginal member of the Royal Family; the even more extraordinarly deferential note struck by political interviewers'.

But we were oblivious to this broader cultural context. Television simply offered better and more easily available entertainment that we had enjoyed before its arrival. I remember once being invited next door to see the boat race on television - this event was then regarded as a great 'national occasion'. But eventually, like everyone else we bought a television. It still offered quite restricted programming (it closed down for an hour in the early evening to allow children to go to bed) and there were intervals when a kitten would play with a ball of wool or the sea would beat on the rocks on a potter would work on a wheel. All very unsophisticated by today's standards, but fascinating enough at the time. Television soon displaced the cinema in terms of leisure time where in any case the screen was often obscured by a drifting cloud of smoke from cigarettes.

Was Christmas more special then or does it always seem that way to a child? As I watched our three granddaughters unwrap their presents at Christmas 2002, our eldest daughter reminded me, 'It's really for the children.' Toys were in short supply in the immediate post-war period, so Christmas was always looked forward to for what it would bring, in one year a much desired train set. Presents I could always expect included boxes of confectionery (e.g., from Fry's) and the Eagle annual. The Eagle was a supposedly wholesome boys' comic which featured the Mekon, a Venusian evil doer who was always ultimately vanquished by 'Dan Dare'. For adults, of course, if Christmas was on a Wednesday as it was in 2002, this meant working on Monday and Tuesday and then back to work on Friday. No holiday shutdown then and no public holiday for New Year's Day.

A reader of this page has contributed some fascinating memories of growing up in Woolwich. He writes, 'I was born in 7, Hough Stret, Woolwich, and I mean IN, as I was born in our old house, the mid-wife was nurse Day in 1946. I attended St.Mary's Primary School, the Headmaster of which was Mr. Rablah and I still recall a master by the name of Mr. Scholah recounting stories of his time in Africa to us. I took the 11 plus exam and attained a 'Governors Place', a somewhat grey area between Grammar and Central Schools. I remember applying to both Askes and Shooters Hill Grammar Schools and being turned down (it was the war bulge they told me!) I ended up going to Bloomfield Central School as it was then known, later to join with Plum Lane Secondary (a School which was frowned upon as being far below us) at the beginning of my third year. The Headmaster was Mr Tom Smith who ruled the school with an iron fist in those early days, and to be sent to his study for punishment was worse than a visit to the National Health Dentist in Market Street.

Hough Street was situated between "The Square" and the old ferry and had its own distinct personality, somehow different to any other street, with Woolwich Polytechnic School at one end and "the bomb site" at the other which bordered on to Beresford Street. We protected our street by any means possible and woe betide any kids from around who tried to come and play in our street without an invitation.

It was a true working class area, and quite a few of the residents made a living on The Square, names that come to mind are the Skinners who had a wet fish stand, and the DeLieus (hopefully spelt correctly) and Baldry's. My father who was born and bred in Woolwich affectionately referred to them as 'The Square Heads'. I revisit the old area whenever I manage to go 'home' (from California) either on business or just a vacation. I stand and in my mind's eye picture as it used to be, Mrs Dennard screaming over the wall for 'Keefy' (Keith) or yelling Mrs Cowdrey yelling at the kids to stop kicking their football against her wall. The local pub was the Union Tavern in Creton Street. The landlord's name was Jack Burley and it was here that Dad and most of the other Dad's would go for Sunday lunch as it was known.

There was never enough money when I was a kid, but I can never remember going hungry, or a Christmas without presents. Christmas, now that was a time to remember back then. All the stalls on the square filled with Christmasy fare like nuts and dates and tangerines, and the stalls that used to appear selling toys. Powis Street and Hare Street lit up with Christmas lights together with all the stores, and looming above it all was the tower of the Co-op building, with its illuminated clock which was never quite on time. On Xmas morning most of the front doors of the houses would be left open and people would go from house to house exchanging greetings and having a tipple, no invitation neede here, you just walked in. Dad would smoke cigars, an aroma I adored and still associate with Christmas to this day. Brian, my elder brother and I had to wear our new suits purchased specially for Christmas. By toady's standards we were poor, but we were happy and content and appreciated the small things.

We moved to Eltham when I was 14 as they wanted to demolish all the houses to make way for offices. Our new home in Westhorne Avenue actually had an inside toilet with a built in bathtub, what a novel concept!'

A contributor from Ontario, referring to the Links picture on this site, writes, 'It just so happens that I spent the years 7-17 growing up directly behind the furthest end of that building (Macoma Road) from 1942-1951. And before that from 1938-1942 on the street (Macoma Terrace) that intersects the row of houses beyond the Links. In the war years the Common across from the Links was home to an underground air raid shelter which I hated to go into, if there was an air raid while coming from Ancona Road school. It was very deep, dark and smelly. I would either race home or try to stay near the top of the stairs. In the latter case I was usually ordered down the stairs by an ARP men. There was a barrage balloon site on the Common as well. My friend Roy (who lived in Tuam Road) and I played a game whenever the sun was out and a balloon was aloft. It went like this: in the shadow of the balloon we could wrestle; when the sun moved and we were exposed to sunlight we had to break off and race for the shadow and start over. Great fun.'

'I had just started at Plumcroft school (then Plum Lane) when the Blitz began in September 1940. I came out of the school air raid shelter (under the upper kindergarten school building) around 5 p.m. to see the whole of the docks on fire, as well as the school just below me. That was traumatic for me, I'd lost my new satchel, crayons, pencils and all - up in smoke! My dad worked for the CWS in Silverton Docks and normally arrived home about 4 p.m. He didn't arrive until 11. We didn't have telephones in those days so that was pretty traumatic for my mother who had lost her first husband in World War 1.'

'I also clearly remember watching the Battle of Britain from the garden of 5 Macoma Terrace - until a German fighter came down in flames to crash down Hudson Street way somewhere. I also remember going to see the wreck and putting money in the can for the Spitfire Fund. For years I used a very nice students desk that was salvaged fron the ruins of the houses that stood opposite the Common between the almshouses and the Old Mill pub. The houses were quite handsome but were demolished by a land-mine (parachute bomb) during a night raid I believe.'

Nostalgia has been defined as a 'bittersweet, selective longing for things, persons or situations of the often idealized past.' There are four forces that may contribute to such a longing for an idealised past:

Leamington historian Bill Gibbons expressed the appeal of nostalgia well when he said, 'A lot of people are attracted to things of the past because you are leaving the conflicts and doubts and worries of the present, and by going back there are no decisions to make - it's all happened. In a way, it's a much more safe atmosphere.' A contributor to this page commented, 'Nostalgia is only good for eleven years. After that places and people become unrecognisable.' This page started by recalling how in many ways relatively little had changed in the road in which I lived some fifty years ago. But in the meantime I have changed a great deal. This was brought home to me recently when I was talking to a young friend about accents and I remarked that I once had a London accent. 'Don't talk utter rubbish, Wyn', she replied, 'you've never had a London accent in your life.' The more we change, and the more 'globalisation' accelerates and accentuates pressures for change, the more we may want to cling to identities from the past - even if contemporary friends may see them as constructed, retro and down market identities.

On this general theme, for an 'urban angst' vision of contemporary South-East London life, a readable blog (the author is apparently a journo, not that that is necessarily a recommendation) with some good links can be found at Casino Avenue

Contact me by E mail I have had some interesting messages recently which have allowed new material to be incorporated into the page.

The number of visitors (since the counter was re-set, apx. 5,500 before then) is

w.p.grant

Or at the

Rose of Denmark, before home

games at Charlton